A hundred rupees invested in a new share sale, or initial public offer (IPO), at the turn of the millennium often doubled or tripled the moment the shares were listed. That meant you could have made more money by selling shares immediately on listing than you would have by locking your capital in a fixed deposit for years.

If you blindly invested in any IPO in the last decade and half, you would have made positive returns at the opening bell in three out of four instances.

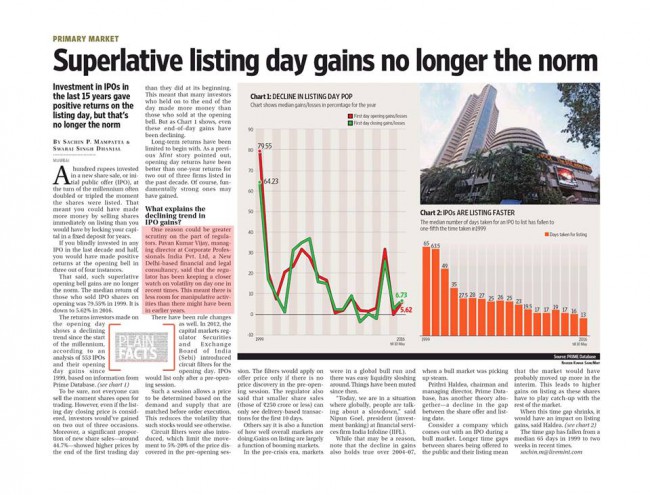

That said, such superlative opening bell gains are no longer the norm. The median return of those who sold IPO shares on opening was 79.55% in 1999. It is down to 5.62% in 2016. The returns that investors made on the opening day shows a declining trend since the start of the millennium, according to an analysis of 553 IPOs and their opening day gains since 1999, based on information from Prime Database.

To be sure, not everyone can sell the moment shares open for trading. However, even if the listing day closing price is considered, investors would have gained on two out of three occasions. Moreover, a significant proportion of new share sales—around 44.7%—showed higher prices by the end of the first trading day than they did at its beginning. This meant that many investors who held on to the end of the day made more money than those who sold at the opening bell. But as Chart 1 shows, even these end-of-day gains have been declining.

Long-term returns have been limited to begin with. As a previous Mint story pointed out, opening day returns have been better than one-year returns for two out of three companies listed in the past decade. Of course, fundamentally strong ones may have gained.

What explains the declining trend in IPO gains?

One reason could be greater scrutiny on the part of regulators. Pavan Kumar Vijay, managing director at Corporate Professionals India Pvt. Ltd, a New Delhi-based financial and legal consultancy, said that the regulator has been keeping a closer watch on volatility on day one in recent times. This meant there is less room for manipulative activities than there might have been in earlier years.

There have been rule changes as well. In 2012, capital markets regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India introduced circuit filters for the opening day. IPOs would list only after a pre-opening session. Such a session allows a price to be determined based on demand and supply that are matched before order execution. This reduces the volatility that such stocks would see otherwise. There were also circuit filters introduced which limit the movement to 5-20% of the price discovered in the pre-opening session. The filters would apply on offer price only if there is no price discovery in the pre-opening session. The regulator also said that smaller share sales (those of Rs.250 crore or less) can only see delivery-based transactions for the first 10 days.

Others say that it is also a function of how well overall markets are doing. Gains on listing are largely a function of booming markets. In the pre-crisis era, markets were in a global bull run and there was easy liquidity sloshing around. Things have been muted since then.

“Today we are in a situation where globally people are talking about a slowdown,” said Nipun Goel, president – investment banking at IIFL.

While that may be a reason, note that the decline in gains also holds true over 2004-07, when a bull market was picking up steam.

Prithvi Haldea, chairman and managing director at Prime Database, has another theory altogether—a decline in the gap between the share offer and listing date.

Consider a company which comes out with an IPO during a bull market. Longer time gaps between shares being offered to the public and their listing mean that the market would have probably moved up more in the interim. This leads to higher gains on listing as these shares have to play catch up with the rest of the market. When this time gap shrinks, it would have an impact on listing gains, said Haldea.